[ad_1]

The COVID-19 pandemic hit state budgets particularly hard in 2020, with $ 24.11 billion in tax revenue collected from 2019 levels. But analysis of data from the National Association of Commissioners Insurance (NAIC) shows that insurance regulation has remained a profitable source of state revenue, generating $ 3.29 billion in budget surpluses in all 50 states and the District of Columbia, up from $ 2.94 billion in 2019.

According to data from the Federation of Tax Administrators, total state tax revenues fell 2.2% from $ 1.090 billion in 2019 to $ 1,066 billion in 2020, with Utah (down 12.4%), North Dakota (down 12.8%) and Alaska (down 26.0%) the hardest hit. In total, 31 states and the District of Columbia saw their tax revenues plummet, with California alone falling by $ 16.27 billion.

In contrast, the NAIC 2020 Insurance Department Resources Report shows that state insurance departments collected $ 3.77 billion in regulatory fees and assessments, up 12.9% from $ 3.34 billion in 2019. Combined with the $ 190.6 million in fines and penalties collected by the departments (roughly stable from 2019) and $ 1.07 billion in miscellaneous “other†revenue, the insurance departments of the State generated $ 5.03 billion in total revenue, more than three times the $ 1.60 billion they actually spent on insurance regulation.

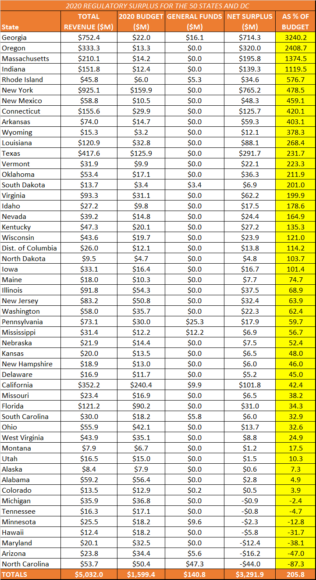

This “regulatory surplus” of $ 3.43 billion (up 11.8% from $ 3.07 billion in 2019) must be weighed against the $ 140.8 million in funds that the departments insurance companies withdrew general funds from their states, themselves up 5.4% from 2019. But even after subtracting that total, insurance regulation remained a profit center for states, with 3 , $ 29 billion in excess revenue, up 12.1% from $ 2.94 billion in 2019.

A tax of any other name

Revenues collected by insurance departments, whether from fees and assessments, fines and penalties, or funds from other sources, should not be confused with the taxes that states assess. on insurance premiums. All states collect taxes on premiums written in that state, and most also collect “retaliatory” taxes, charging out-of-state insurers at the rate set by their state of domicile if it is higher than the rate. rate of the jurisdiction where the premium is written. The existence of retaliatory taxes pushes most insurers to locate in relatively low tax jurisdictions. The states with the highest and lowest effective premium tax rates in 2020 are shown in the graph above.

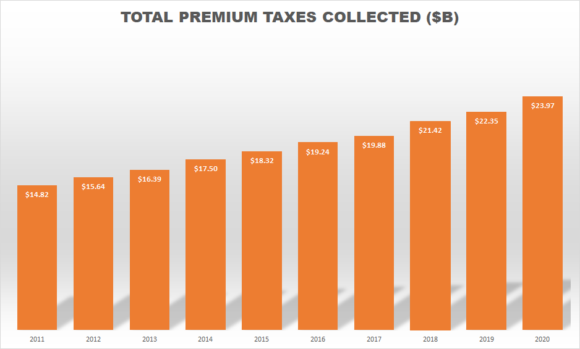

Premiums and retaliation taxes are deposited into a state’s general fund, just like other sales taxes. Kansas is a partial exception, in this regard, as the Kansas Department of Insurance retains 1% of premium taxes collected, which it reports as “other” income. As the chart below shows, premium taxes have been a stable and largely recession-resistant source of revenue for states, increasing 61.7% over the past decade to $ 14.82 billion. in 2011 to 23.97 billion dollars in 2020.

But as noted, the fees and fines collected by insurance services far exceed the amounts strictly necessary to support regulatory activities. In 2020, only seven state insurance departments (North Carolina, Arizona, Maryland, Hawaii, Minnesota, Michigan, and Tennessee) generated less revenue than the combination of what they spent on regulation and what ‘they received from the general fund of their state. In fact, the total amount states spent on insurance regulation in 2020 ($ 1.36 billion) was only 31.8% of the revenue that insurance regulators collected.

The rest of the funds – the so-called “regulatory surplus†– amounts to a hidden tax on insurance companies, which is ultimately passed on to consumers in the form of more expensive coverage.

Follow the money

State insurance departments differ in how their budgets are structured and what happens to funds raised by regulators. A small majority of states (27 in total) use “dedicated†budgets, in which revenues are paid into a separate account that is carried over from year to year. If the revenue paid to the account exceeds the budget allocated by the state legislature for that year, the surplus is carried over to subsequent years and can be used to cover future departmental deficits.

In theory, the advantage of a dedicated financing system is to reduce cyclical fluctuations in income. For example, a department could collect large fines and penalties that constitute a one-time windfall. For example, Texas reported that $ 19.2 million of the $ 67.6 million in fines and penalties the state collected in 2020 came from a single entity, while Vermont noted that A significant settlement was $ 1.8 million of the $ 2.2 million in fines he reported.

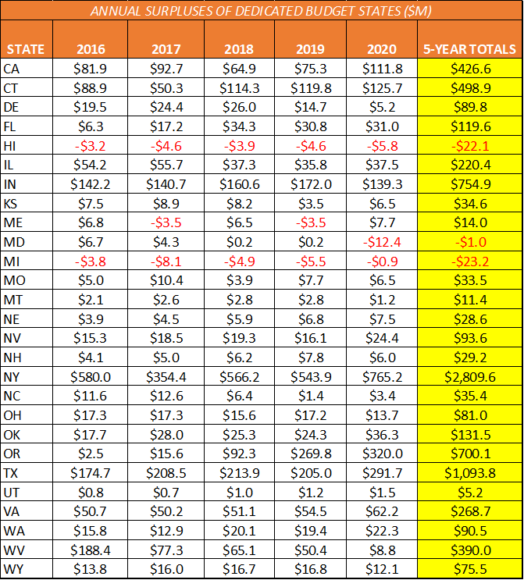

A dedicated fundraising budget should also theoretically alleviate any need for a ministry to cut spending or draw on general funds from the public treasury. But as the table below illustrates, there are discrepancies between this theoretical account and the performance of departments with dedicated budgets in the real world.

As is evident, the vast majority of dedicated budget states – 24 out of 27 – have generated more revenue than they spent on insurance regulation in each of the past five years. Two other states, Hawaii and Michigan, have recorded deficits in each of the past five years. Only Maine and Maryland actually behaved as the notional account predicts, running deficits in some years and surpluses in others.

In addition, in some cases, the surpluses are really huge. The cumulative five-year surplus of $ 2.81 billion generated by New York, or the five-year surplus of $ 1.09 billion generated by Texas, cannot reasonably be called a prudential “rain fundâ€. Both states are clearly overcharging insurers and insurance producers for huge regulatory and licensing fees.

The notional account is also underestimated by the fact that four of the states with budgets dedicated to insurance departments have nevertheless also received at least part of the funds from their states’ treasury over the past five years, although four posted surpluses each year. Two of these departments received very limited general funds, none in 2020. (Oklahoma received $ 1.6 million in general funds in 2016, but none in the past four years. Washington received around $ 500,000 in 2016 and 2017, but none in the past three years.)

California, which often derives a small portion of its annual budget from the public purse, has raised $ 21.6 million in general funds over the past five years. The real outlier is North Carolina. Although it posted a combined surplus of $ 35.4 million over the past five years, the ministry also withdrew $ 209.8 million from general state funds over the same period.

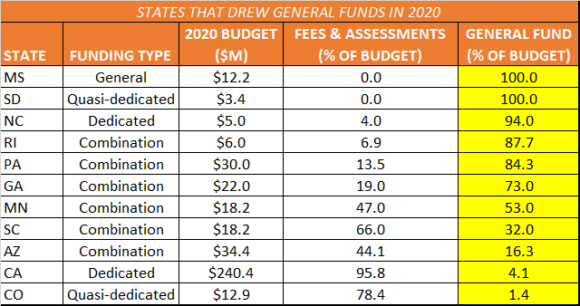

Only 11 states drew general funds from their public treasuries in 2020, but they came from the four types of budgets identified by the NAIC: dedicated (covered above), quasi-dedicated (excess revenue is deposited into the general account each year. state), general (all operating funds are allocated directly by the state), and “combination†(the department’s budget rules employ a combination of two or more of the other types).

While Mississippi and South Dakota are the only states that get 100% of their funding from the general fund, only Mississippi is formally classified as a “general fund†state, a change came into effect in 2017. Notably, As Mississippi continues to collect fees and contributions from businesses, as of 2020 it no longer reports those funds, all of which are deposited into the state’s general account.

Despite Mississippi’s failure to report regulatory fees and the contributions it collects, for the 23 states (and the District of Columbia) that do not employ dedicated budgets, the budget surpluses generated by insurance regulation still serve more directly tax. Surplus funds are usually, but not always, deposited in the government’s treasury. There are some partial exceptions. Arkansas allows the department to carry over surplus funds for one year, but returns any surplus to the general fund every two years. Alaska and North Dakota both allow their departments to carry over $ 1 million to the next year, with the rest going to the general fund.

Of the states without dedicated funds, only Arizona and Tennessee spent more on insurance regulation than they generated revenue in 2020. Collectively, this cohort of jurisdictions generated $ 2.87 billion in revenue. . Net of the $ 454.4 million they spent on regulation and the $ 83.5 million they took out of general funds, these states enjoyed a cumulative windfall of $ 2.33 billion. thanks to insurance regulations in 2020.

Conclusion

Below, I list the states in order of insurance regulatory surplus (revenue net of departmental operating costs and general funds transferred from the state treasury) expressed as a percentage of that state’s departmental budget.

Subjects

Loss of profit from COVID-19 legislation

[ad_2]