Lincoln is home to the largest population of Yazidi refugees in the United States, numbering in the thousands. Among them is Husker Falah Rashoka, who served in the US military in Iraq. Today, as a doctoral student in nutrition and health promotion at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, he has turned to research to help his community overcome barriers to health care.

To identify barriers first, Rashoka and her advisor, Megan Kelley, formed a Midwest focus group that includes members of the Yazidi community, health care providers and social workers. Recently, they published an article in the International Journal for Equity in Health, using qualitative analysis of focus group discussions to establish broad themes – informational barriers, resource barriers, social barriers, effects of barriers, and need for education – how they interact with one another, and the strategies that can help mitigate them.

“The initial aim of these information gathering sessions was to identify what was most influential in terms of access to care, and based on what we found we developed an initial set of materials education on access to health care,” said Kelley, an assistant professor in the College of Education and Humanities. “I think one of the big takeaways is the importance of including community members in decision-making and having people around the table where policies and programs are designed for them. “

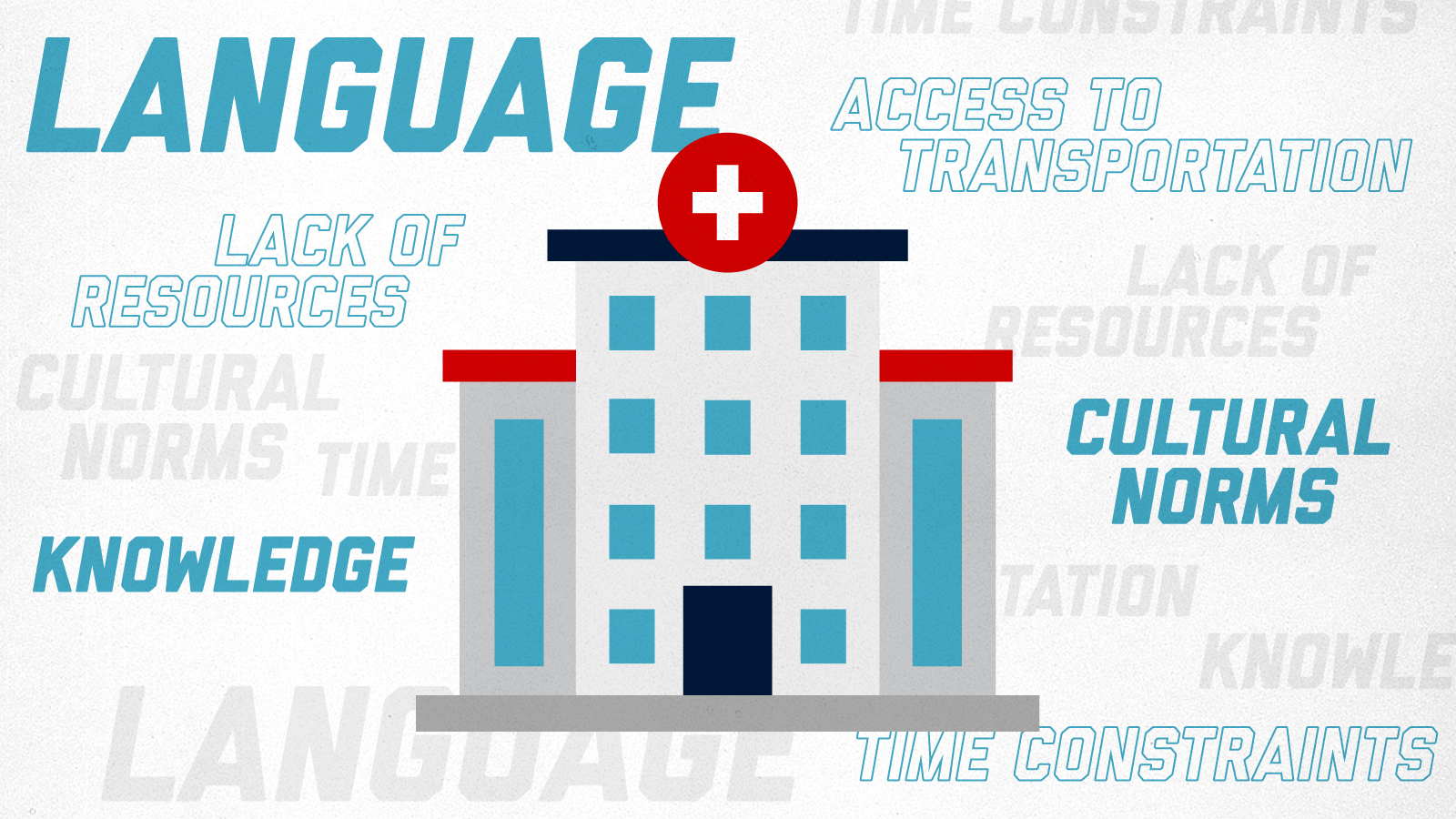

According to the focus group analysis, language plays an outsized role, as Yazidis speak Kurmanji and translators are not always familiar with this dialect.

“Language is a main obstacle,” Kelley said. “The way people communicate affects all levels of access to care, from finding information about available resources, to calling and making appointments, or learning about the type of services offered. , communication with your supplier. Added to this is the question of how the system works, because it is a complex system. »

Language also interacts with past experiences and has caused confusion regarding the healthcare system in the United States, as lack of knowledge of the system has also been cited as a major barrier.

“The Yazidi community health care system in Iraq is a general health care system, where anyone can go to a doctor or a clinic for free,” Rashoka said. “When they moved to the United States, they had to deal with a big change in the system, which is a private system with things like health insurance or Medicaid.”

Additionally, Rashoka said, although often confused with other ethnic groups in the Middle East, Yazidis have cultural norms, including gender norms, that are different, but few understand them.

“I think cultural norms are important that a lot of people aren’t aware of, and in terms of some people not seeking care – or mental health services – that’s a problem, and that’s is more important than we imagine,” Rashoka said. “Men will avoid seeking mental health care, for example, because they think it’s not strong.”

The focus group research also identified other barriers, including transportation, time constraints due to work and family responsibilities, economic security and others. The article used the socio-ecological model to formulate six recommendations, including culture-specific educational programs and interpreters who are medically trained and linguistically aligned.

“The application of the study results and the recommendations we provided are most important to me,” Rashoka said.

From the group discussions and the recommendations they provided in the article, Rashoka and Kelley have since developed tools to help inform the Yazidi community and the healthcare providers who work with them. While they had planned to hold in-person educational sessions, the covid-19 pandemic shifted their delivery. Instead, they created an educational brochure about the health system that is printed in English and Arabic, combined with phone calls made in Kurmanji. They have also developed a webinar for healthcare providers to educate about the Yazidi community, the various barriers they face and ways to overcome them. As pandemic restrictions permit, Rashoka hopes to hold in-person events to continue her education.

“Part of the reason we want to reach healthcare providers as well is that Yazidi culture is unique,” Rashoka said. “Additionally, we wanted to include as much information as possible about how they can work with people who have experienced terrorism, genocide, a lot of traumatic things in their lives, so we also focused on care taking account of trauma.”

“Providers are knowledgeable about trauma-informed care, and there are screening procedures to identify patients who have experienced trauma,” Kelley said. “But based on our conversations, the experiences of Yazidi patients do not always reflect the expected results of this approach. If you are working with a member of the Yazidi community, they are more likely to have some trauma experience, and extra care should be taken to provide them with safety, choice and empowerment as patients. .

Rashoka and Kelley are collecting data on the use of the tools and their effectiveness and plan to publish the results in the near future.

“There are many organizations in Lincoln and across the state and the country that work and do phenomenal work for marginalized communities like the Yazidi,” Kelley said. “I think this study supports the idea that there is room for more focus, time and funding to expand the organizations doing the work to address these ongoing, systematically identified issues that influence access to care and the health outcomes of our communities. ”